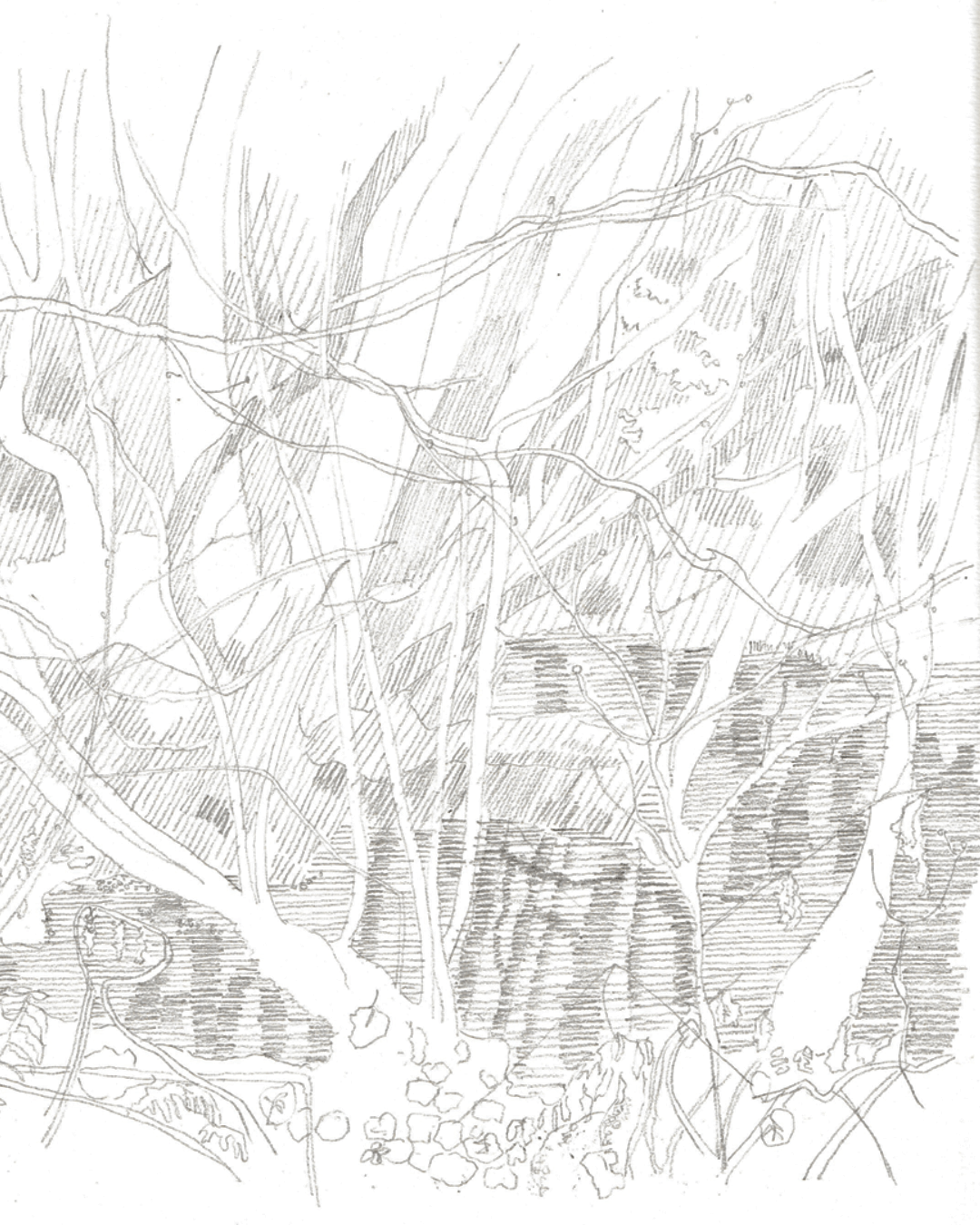

I took the dog for a walk. Knowing I had plenty of time for it, I decided to rediscover a new path I’d recently found. While rambling, I was smugly surprised how easily I was able to retrace my steps, how these paths formed by movement remain obvious; humans, dogs and deer all regularly navigate through these spaces, naturally curtailing growth and treading the earth; forming the path. They are as clearly perceptible as the lorry shapes carved through roadside tree canopies. Then I realised I was a bit lost.

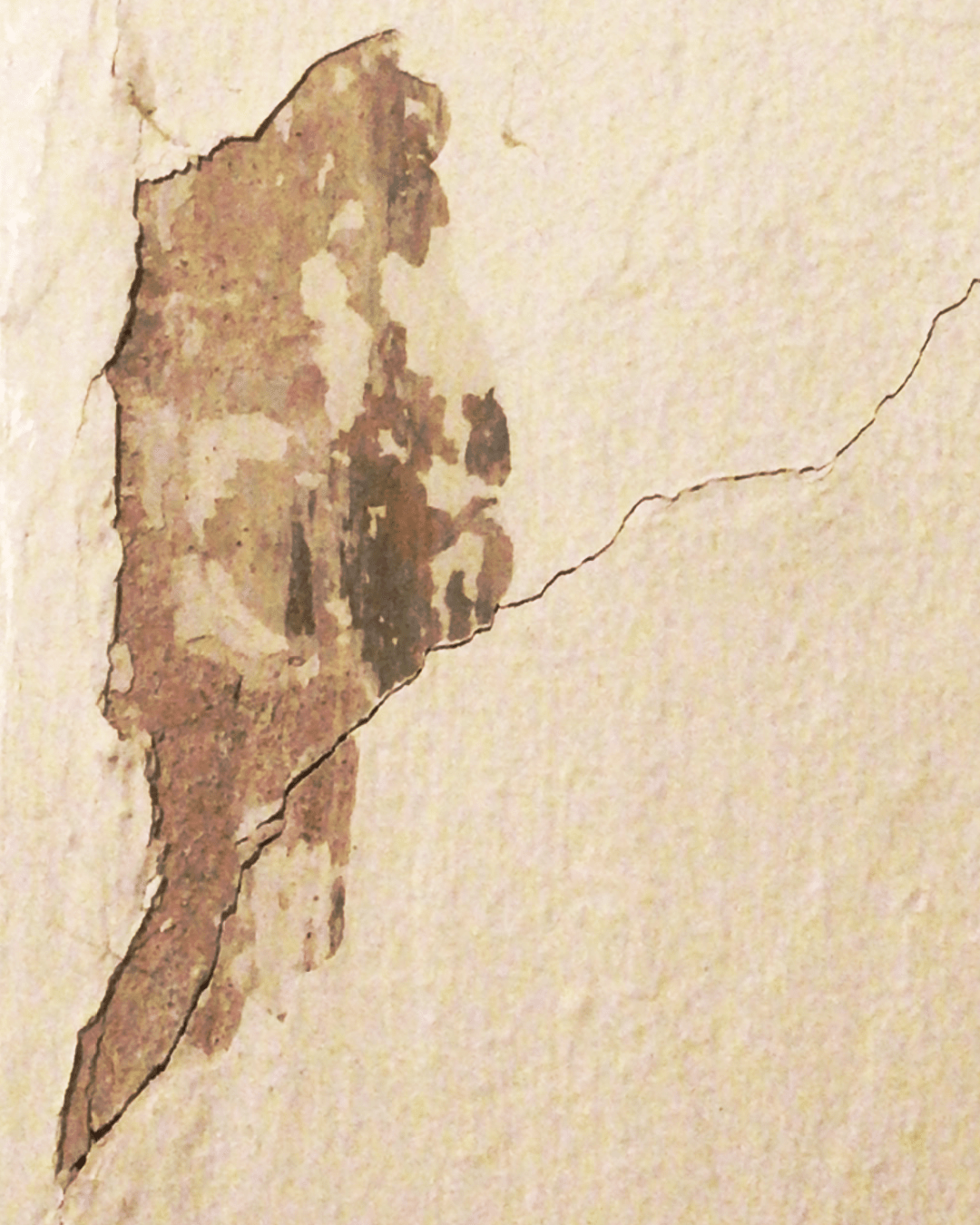

The forest was bounded by heathland on my left, and to my right, was dense forestry woodland, the trees so intensely spaced, it’s plain no creature wanders in there. I dared not look at it. I have a terrible imagination and could easily visualise red eyes glowing through the dark vacuum. So, I persisted on my new path until I eventually found a way out.

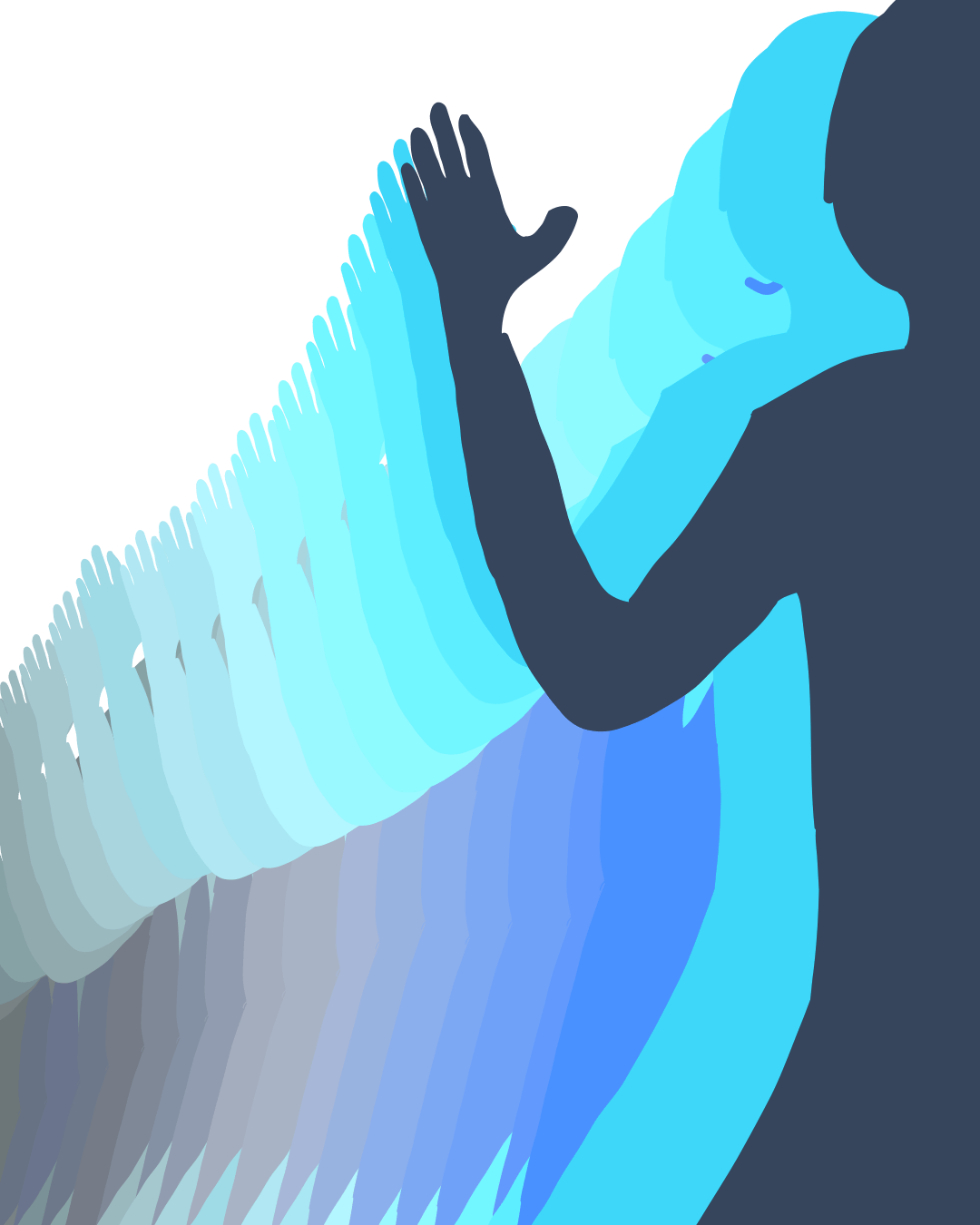

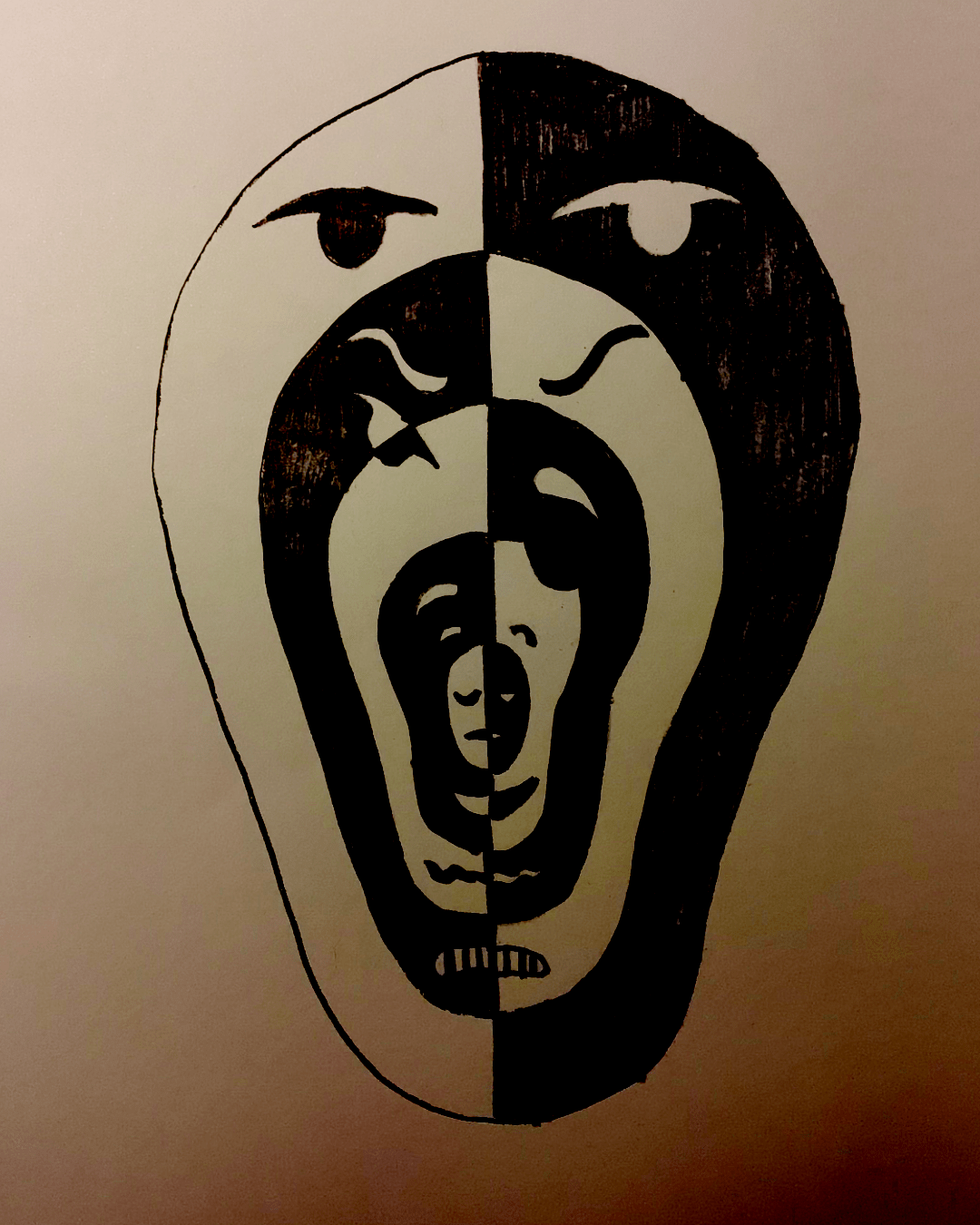

Ideas started swirling, about how maybe our brains are like a forest. We forge paths, emotional responses and ways of thinking, and these paths become increasingly hard to deviate from as trees sprout from the undergrowth and create impassible areas. In this analogy, imagine trauma like a forest fire, or destructive trailblazing. They become maybe the easiest paths to go down, or ones we cannot help but revisit. All paths lead there.

Maybe society is like this too. We function with so many conventions that we take for granted. I think, only hindsight makes you realise this, because I’m certain many awful conventions still exist (of course they do, though I’m thinking about this principally from a western perspective). These conventions are like paths, and trying to deviate from them is difficult. You are going to get scratched, sunk, dirty, scared and probably a bit lost on the way. But once they are forged, others can follow and eventually the path is well trodden. They might even become the new main route.

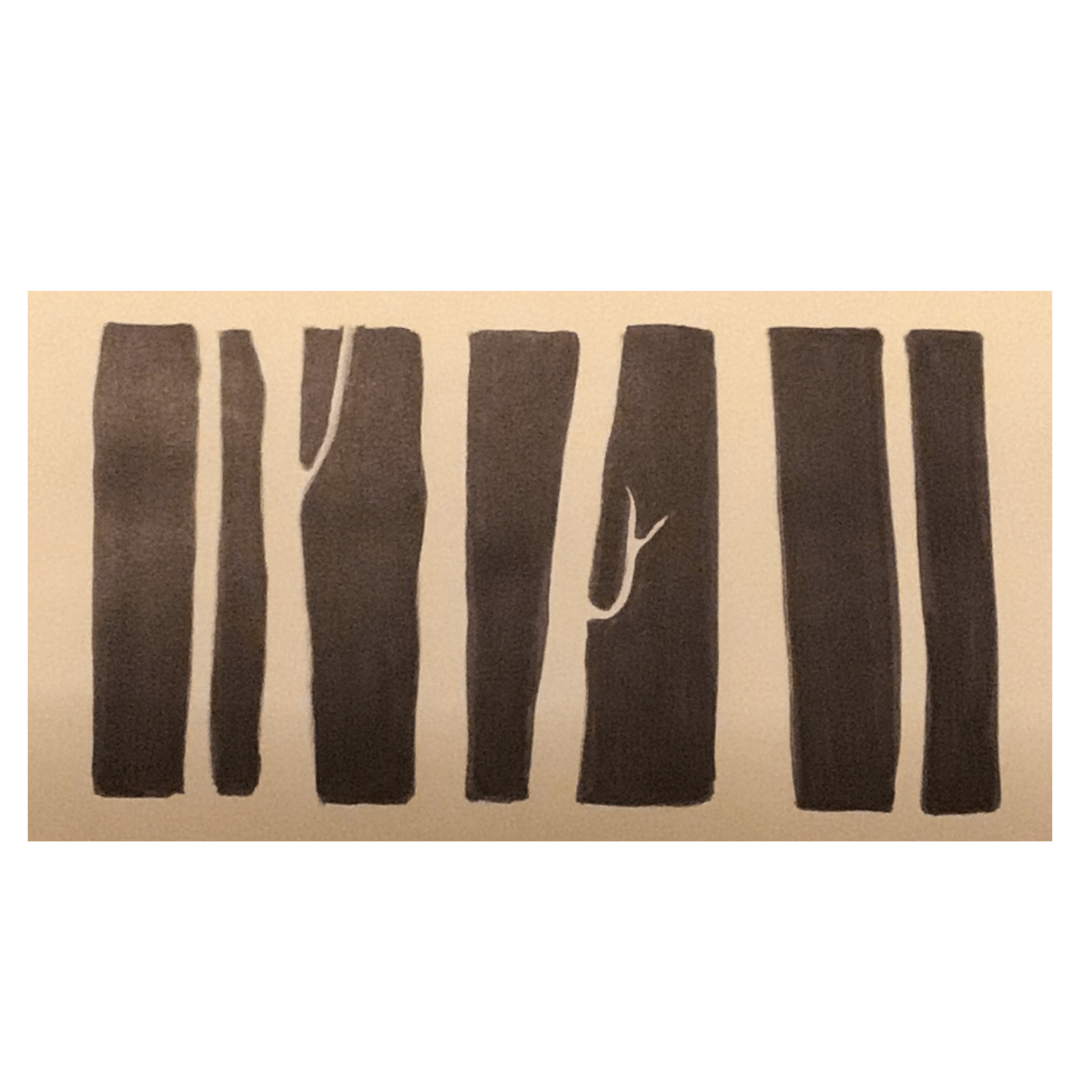

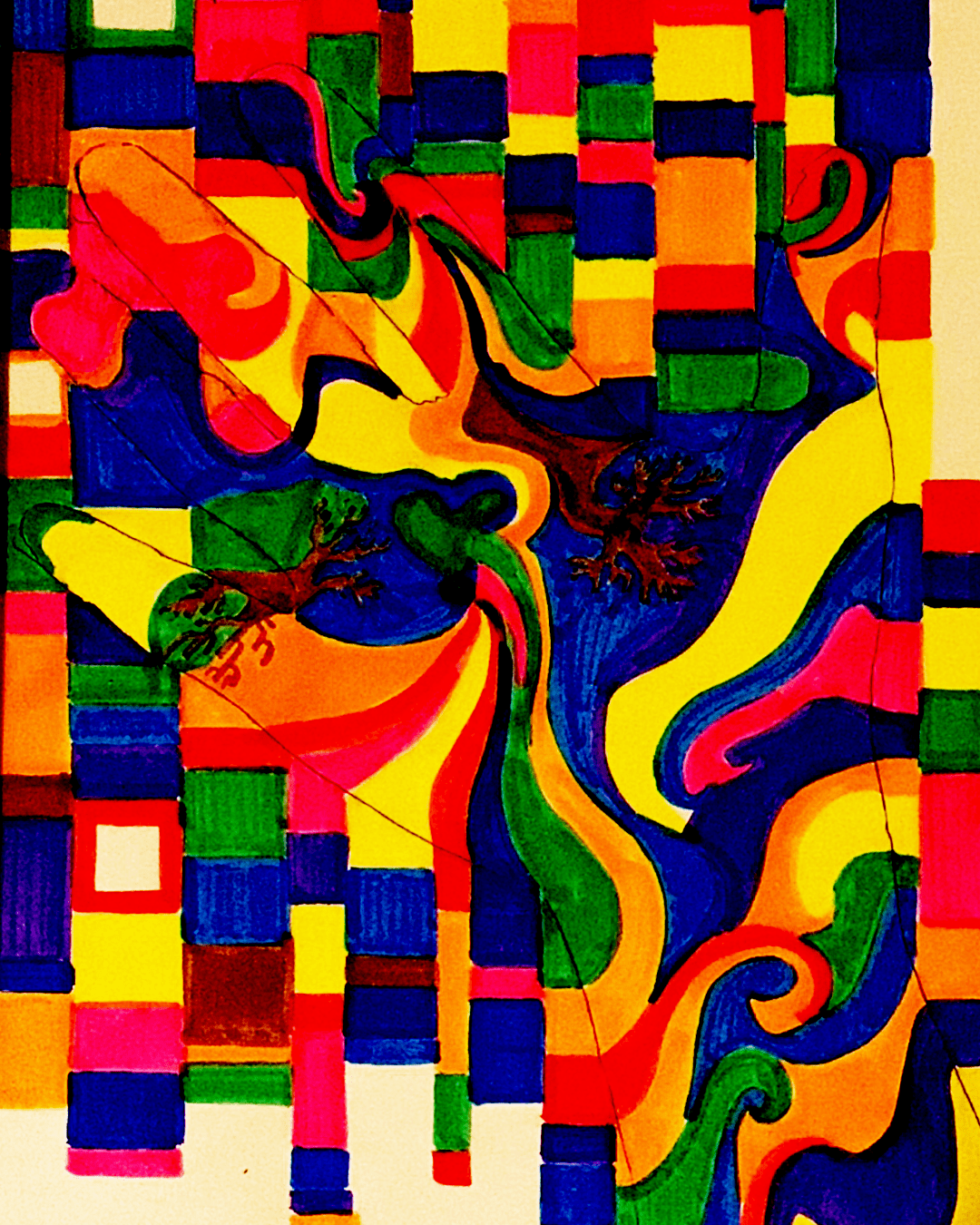

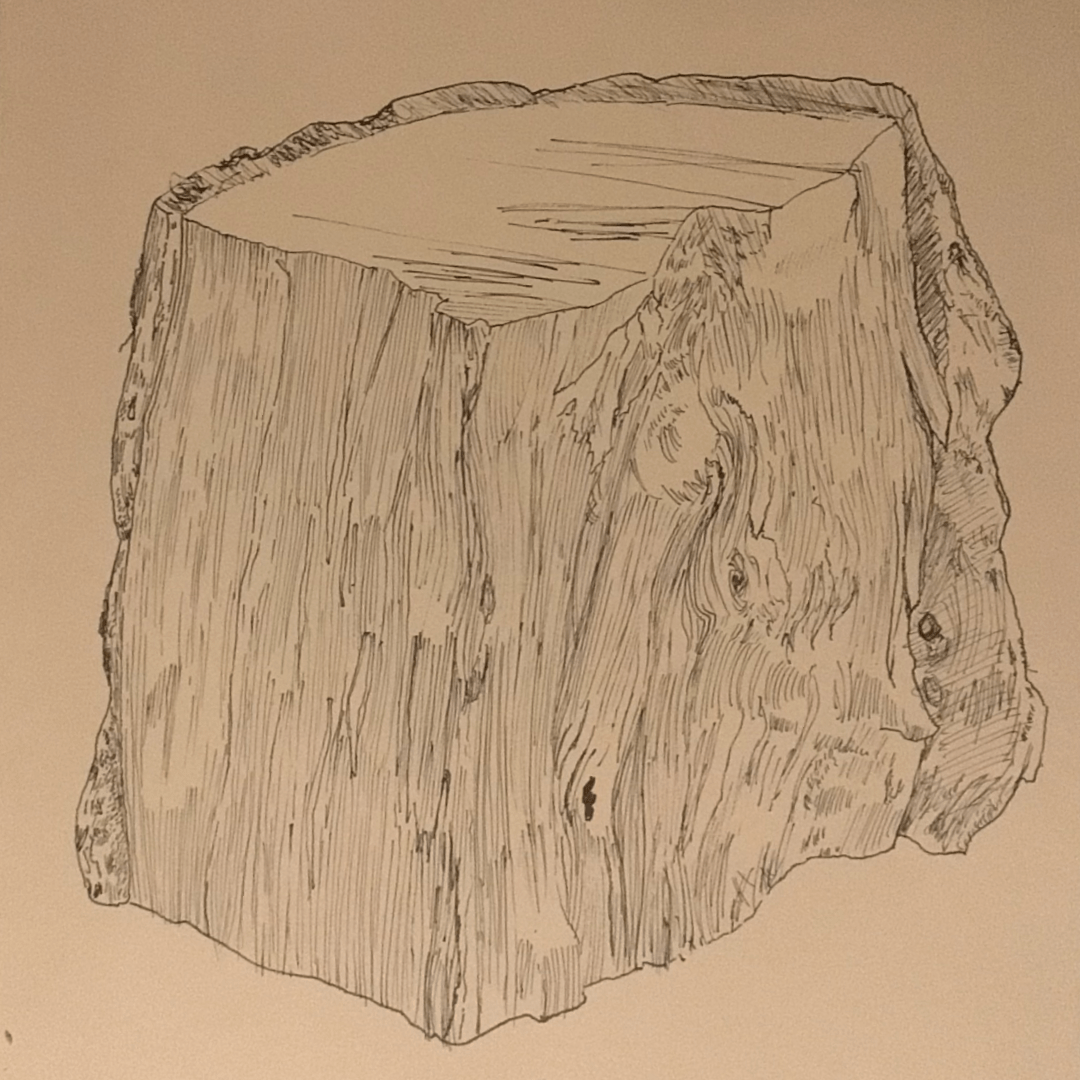

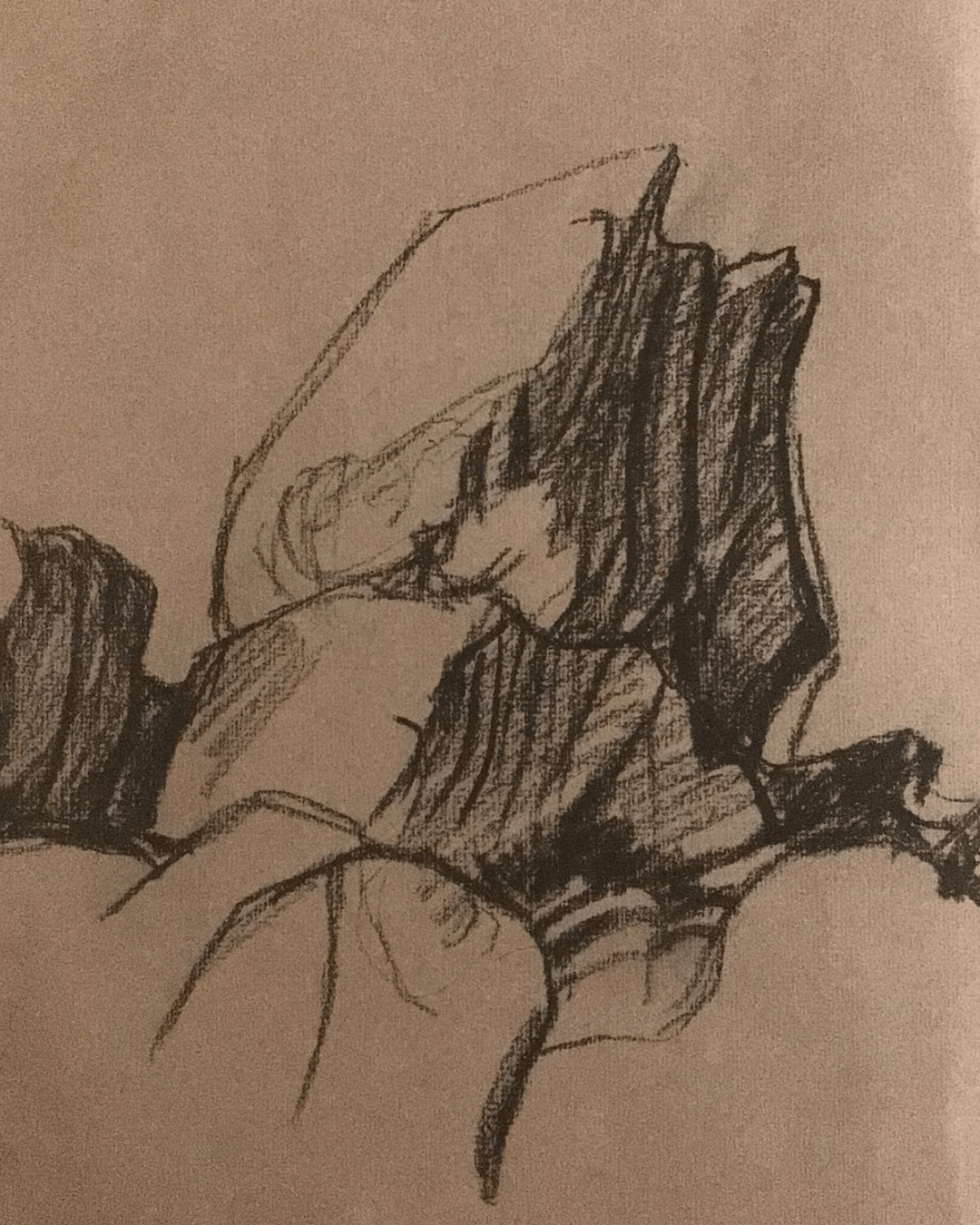

I illustrated these concepts with what I was presented with while lost, the dark forest, appearing as bars of a cage.