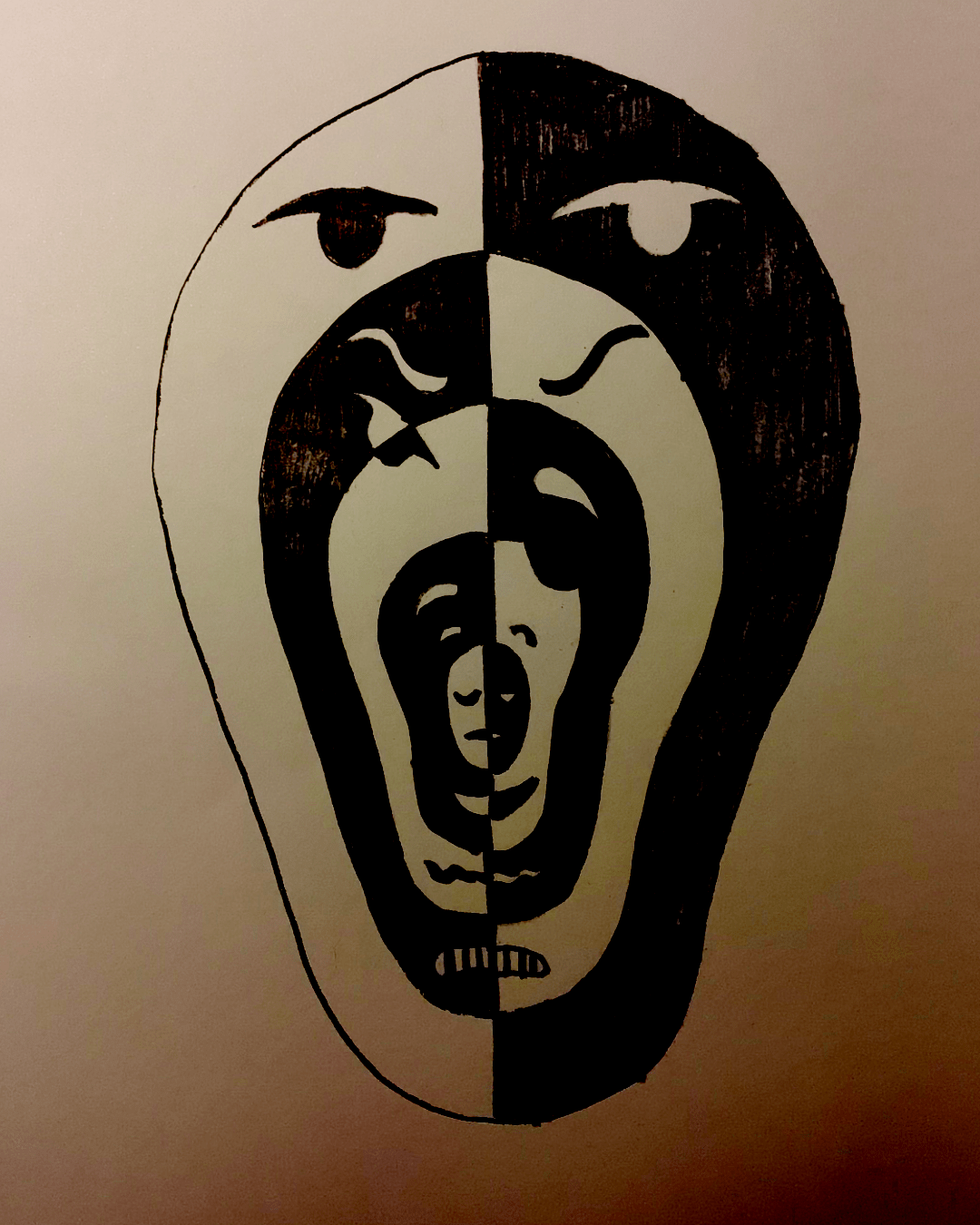

I recently stepped into a building, back in time. Everything in that place had been made by hand, laboured over, and in spite of having gone through the knocks of life, was well preserved. I started thinking about the value of old things, admittedly not a new feeling for someone interested in architectural conservation, but I did feel a perspective shift.

My presumption before was not so precious about older things, insisting somehow that we can also add our own modern (honest?) artistic stamp to older buildings, and, while appreciating the values of what we are working with, we shouldn’t be to nostalgic about loss ‘where it is needed’. But as it becomes more apparent, the skills and labour and materials invested in these buildings of the past should not be so readily subjected to our fashionable whims. These are scarce commodities and we can’t pretend to replace them with anything like the same level of quality.

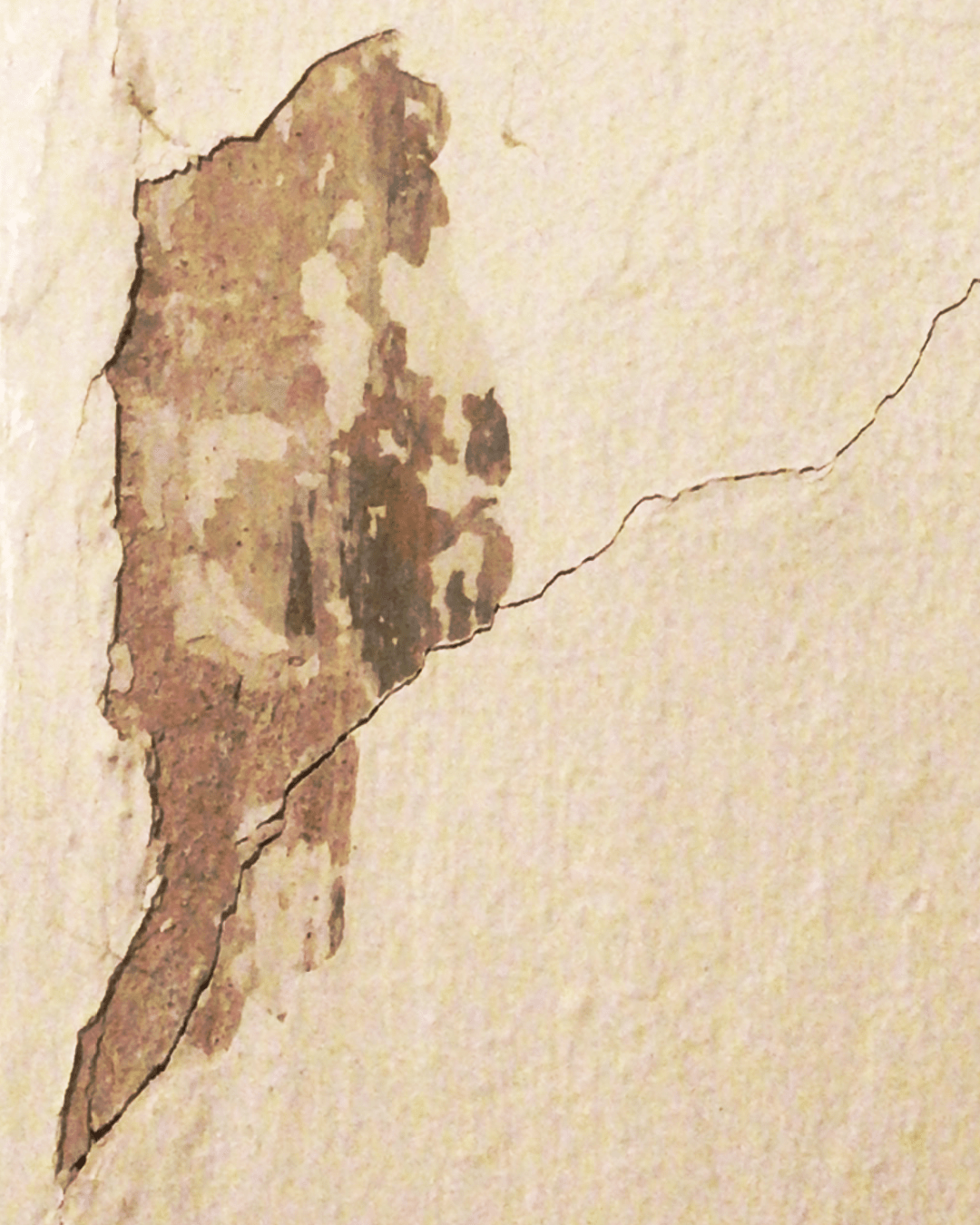

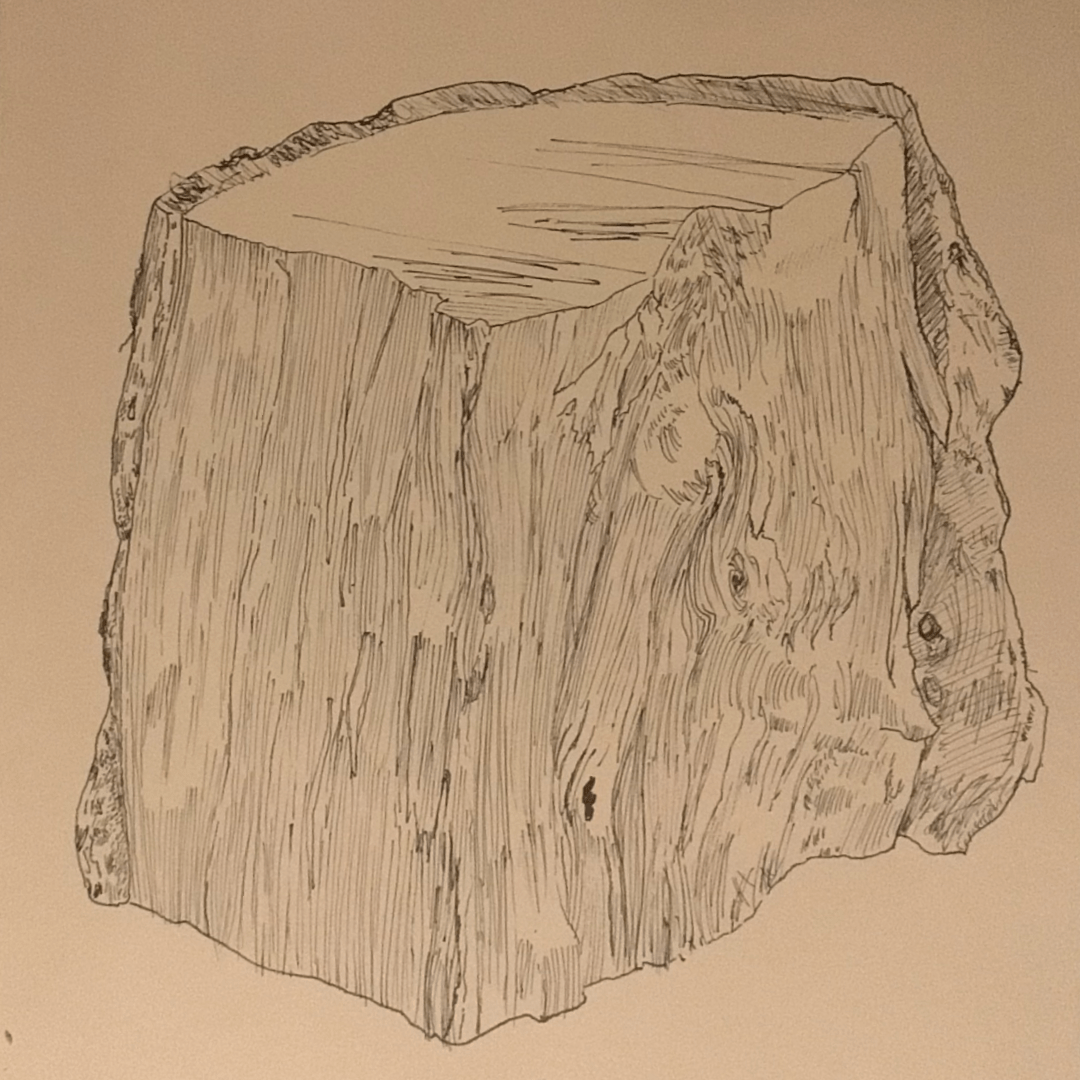

Patina, I think, is like a veneer of use acquired through ages. I used to look at my doors and skirtings and sigh at the knocks left by stubbed toes, chips made by mysterious blunt objects, even little grubby hand marks around the light switches…peeling paint, cracked plasterwork… Some of this requires attention (or cleaning), but actually these marks tell a story of the life of the family within. We are unconsciously stamping ourselves in our time and place.

Because we have the privilege of living in an old house, we have inherited a number of such bumps and scrapes, and it’s likely the next owner might do the same. I’d like to think this can go on and kind of add to the charm of the place. These are not qualities modern buildings and materials are now designed for.

I’m not trying to be black and white about this, after all my own line of work often involves adapting historic buildings. But if we focussed instead on doing something once and doing it well, making something enduring, an investment for the future, how might be do things differently?